The European Recovery Program, universally known as the Marshall Plan, stands as one of the most ambitious and transformative foreign-aid initiatives in modern history.

Enacted on April 3, 1948, when President Harry S. Truman affixed his signature to Public Law 80-472, the plan represented not merely an economic lifeline to war-ravaged Europe but a strategic blueprint for containing the spread of Soviet communism and fostering enduring transatlantic partnerships.Over its four-year span, the program disbursed approximately $12 billion in grants and loans—equivalent to nearly 5 percent of the U.S. gross domestic product in 1948—to sixteen Western European nations, including the United Kingdom, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, West Germany, Italy, and Norway.

The plan’s achievements went beyond raw economic statistics; it laid the groundwork for the modern European Union, cemented American soft-power influence in Europe, and established a precedent for future post-conflict reconstruction efforts. In taking a forward-thinking view, the Marshall Plan offers enduring lessons on the interplay between economic aid, political stability, and regional integration—lessons as pertinent to twenty-first-century challenges as they were to the immediate aftermath of World War II.

World War II inflicted unprecedented destruction on Europe. Major urban centers—London, Dresden, Berlin, Cologne, Hamburg, Rotterdam, and Warsaw, among others—lay in ruins from relentless aerial bombardment and ground combat. Industrial capacity was decimated: factories were either destroyed or operating at a fraction of pre-war output.

Transportation networks—railroads, bridges, ports, roads, and airfields—were extensively damaged, disrupting the movement of goods and people. Agricultural production had cratered, and famine loomed in regions where fields had been torn by battle and farm equipment requisitioned or destroyed. Millions were displaced: refugees, prisoners of war, and survivors of Nazi persecution roamed the countryside in dire need of food, shelter, and medical care.

Politically, the Soviet Union’s Red Army occupied much of central and eastern Europe, establishing closely aligned satellite regimes that eyed Western Europe with suspicion. The nascent United Nations and other multilateral bodies struggled to address immediate humanitarian crises against the backdrop of emerging geopolitical fault lines. By mid-1947, it was clear to U.S. policymakers that Europe’s economic collapse risked political collapse—and with it, the advance of communist parties hungry to fill the vacuum.

On June 5, 1947, Secretary of State George C. Marshall delivered a pivotal speech at Harvard University. In a concise but far-reaching address, Marshall asserted that “our policy is directed not against any country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation, and chaos.” He called upon European nations to devise a comprehensive recovery plan, offering American support to finance reconstruction and revitalize economies.

Crucially, Marshall’s proposal departed from paternalistic unilateral aid; it envisioned a cooperative enterprise in which European states themselves would convene to articulate needs and coordinate efforts across national borders. His speech signaled a strategic shift in U.S. foreign policy toward proactive engagement: rather than waiting for crises to unfold, America would invest in stability abroad as a bulwark against totalitarian ideologies.

Though initially met with skepticism in some quarters—questioning both cost and the wisdom of deep involvement in European affairs—Marshall’s championing of partnership ultimately resonated within the Truman administration and with key congressional leaders.

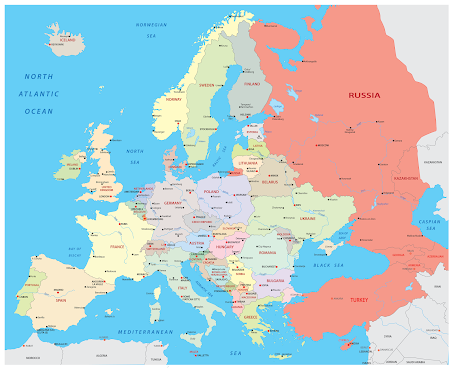

Following the Harvard address, Marshall and his team in the State Department worked in close collaboration with President Truman’s advisors to flesh out the contours of what would become the European Recovery Program. In November 1947, representatives from sixteen European nations—including Britain, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Italy, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, Austria, Greece, Turkey, and the two Germanys—convened in Paris under U.S. auspices to assess needs and allocate resources.

Notably, invitations extended to the Soviet Union and its satellite regimes were declined, as Moscow viewed the program as an unwarranted intrusion into its sphere of influence. Based on the Paris discussions, President Truman formally requested $17 billion in economic and technical assistance from Congress. After vigorous debate over scope, cost, and constitutional authority, Congress enacted the Mutual Defense Assistance Act, which included $5 billion in initial funding.

By March 1948, Congress had approved approximately $13 billion in aid, and on April 3, 1948, Truman signed the legislation into law. The Economic Cooperation Administration (ECA), led by diplomat Paul G. Hoffman, was established to oversee disbursements, monitor compliance, and ensure coordination with recipient governments.

Aid under the Marshall Plan was distributed on a per-capita basis, with adjustments reflecting each nation’s industrial capacity and strategic importance to the overall recovery. The largest beneficiaries were the United Kingdom (approximately 26 percent of total funds), France (about 18 percent), and West Germany (roughly 12 percent), reflecting both their sizable populations and central roles in continental trade networks.

Italy, though aligned with the Allied victory, received a smaller share per capita, partly due to concerns over political instability and the presence of a strong domestic Communist Party. Neutral countries such as Switzerland and Sweden received token assistance. In total, the program committed some $12.4 billion in grants and loans—equivalent to over $130 billion in today’s dollars—along with technical expertise, food, fuel, and machinery.

Recipients were required to draft multi-year economic plans, reduce trade barriers among themselves, and liberalize markets to facilitate intra-European commerce as well as exports to the United States. The ECA conducted regular progress reviews, and funds were released contingent upon demonstrated implementation of agreed policies.

By the program’s conclusion in 1952, Western Europe had experienced notable economic resurgence. Industrial output in participating nations rose by an average of 35 percent above 1938 levels, and aggregate gross domestic product grew at an annual rate exceeding 4 percent—remarkable, given the baseline of destruction.

Transportation tonnage surpassed pre-war figures, and energy production rebounded robustly, alleviating chronic shortages. Agricultural yields improved, mitigating food insecurity. Importantly, intra-European trade surged, aided by the removal of tariffs and the establishment of payment clearing mechanisms. Though the Marshall Plan’s direct financial contribution represented less than 3 percent of cumulative recipient incomes during the four-year period, it catalyzed private investment and industrial modernization.

Skeptics had argued that Europe might have recovered organically as pent-up demand and latent industrial capacity rekindled activity; however, the plan’s infusion of capital and confidence is widely credited with accelerating the timeline of reconstruction by several years, thereby stabilizing fragile governments and deterring communist electoral gains.

Beyond economics, the Marshall Plan played a decisive role in crystallizing the Western alliance against Soviet expansion. The refusal of the Soviet Union and its Eastern European satellites to participate deepened the schism that Winston Churchill famously termed the “Iron Curtain.” The plan’s emphasis on economic integration and political cooperation laid the foundation for what would become the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation (OEEC) in 1948 and, later, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Moreover, the visible success of the program galvanized support among European leaders for a collective security arrangement, culminating in the North Atlantic Treaty of April 1949. With American soldiers and military hardware now stationed in Western Europe, the Marshall Plan underscored the United States’ enduring commitment to European defense and democratic governance. In this sense, the initiative blurred lines between purely economic aid and broader geopolitical strategy, forging a nexus of interests that endured throughout the Cold War.

Despite its successes, the Marshall Plan was not without controversy. Critics contended that the United States had overreached, imposing American commercial and political models on sovereign nations. Some feared that the requirement to purchase U.S. goods under aid provisions hindered the development of indigenous industries. In Italy and France, communist parties decried the plan as an instrument of American imperialism.

Internally, U.S. fiscal hawks lamented the burden on the American taxpayer, particularly as Cold War tensions escalated in Korea and Asia. Additionally, the Central Intelligence Agency—then a nascent organization—allegedly diverted up to 5 percent of ECA funds to clandestine operations aimed at bolstering anti-communist elements in key countries, including clandestine support for partisan groups in Eastern Europe. These covert activities, while arguably reinforcing political objectives, blurred ethical lines and complicate assessments of the plan’s purely humanitarian legacy.

Seventy-plus years after its inception, the Marshall Plan’s enduring legacy is evident in both institutional lineage and normative frameworks. The European Union, with its single market and currency union, can trace philosophical roots to the integration imperatives of the OEEC. NATO remains the cornerstone of Euro-Atlantic security, and countless other regional aid programs—from the post-Soviet transformations of the 1990s to modern initiatives in the Middle East and Africa—draw inspiration from the Marshall Plan’s blend of economic stimulus, technical assistance, and policy conditionality.

The Covid-19 pandemic response and the subsequent Recovery and Resilience Facility in the European Union echo Marshallian principles: substantial grants and loans tied to reform plans, coordinated across multiple nations, and aimed at both recovery and structural modernization.

In a world where crises—whether induced by conflict, climate change, or pandemic disease—risk destabilizing societies, the Marshall Plan demonstrates that well-targeted, cooperative aid can yield transformative outcomes, provided there is political will, transparent governance, and inclusive collaboration between donor and recipient.

The signing of the European Recovery Program on April 3, 1948, marked a turning point not only for a continent emerging from the ashes of total war but for the very concept of international assistance as a tool of enlightened self-interest. President Truman’s endorsement of Secretary Marshall’s vision catalyzed an era of prosperity, integration, and collective security in Western Europe—one that stood in stark contrast to the closed, centrally planned economies of the Eastern Bloc.

As global challenges grow in complexity, from economic inequality and climate disruption to geopolitical rivalry, the Marshall Plan offers a timeless template: leverage economic resources, forge multilateral partnerships, condition assistance on democratic and market-oriented reforms, and pursue long-term stabilization rather than short-term relief alone.

By maintaining a forward-thinking orientation—anticipating potential threats, investing early, and empowering local stakeholders—the international community can replicate the spirit of 1948 and, in doing so, shape a more resilient, prosperous, and peaceful future.

No comments:

Post a Comment